Cache in Software System Design — A Practical Guide

By Oleksandr Andrushchenko, Published on

What is caching?

Caching is the process of temporarily storing frequently accessed data in a faster storage layer to reduce latency, save computation, and improve system scalability. Instead of recomputing or refetching data from a slower source like a database or API, a cache serves it quickly from memory or nearby storage.

Why caching matters

- Performance: reduces response times by serving results from memory.

- Scalability: lowers load on databases and services, allowing systems to handle more traffic.

- Cost efficiency: decreases repeated computation and I/O costs.

- Reliability: caches can keep data available even when the origin system is temporarily slow or unavailable.

Types of caching

- Client-side cache: stored in browsers or mobile apps (e.g. localStorage, service workers).

- CDN cache: edge nodes serve static assets and cached API responses closer to users.

- Application-level cache: in-memory caches like Redis or Memcached to store computed data or query results.

- Database cache: internal caching of query plans or buffer pools to speed up reads.

- Operating system cache: kernel-level page and file caches to optimize disk reads.

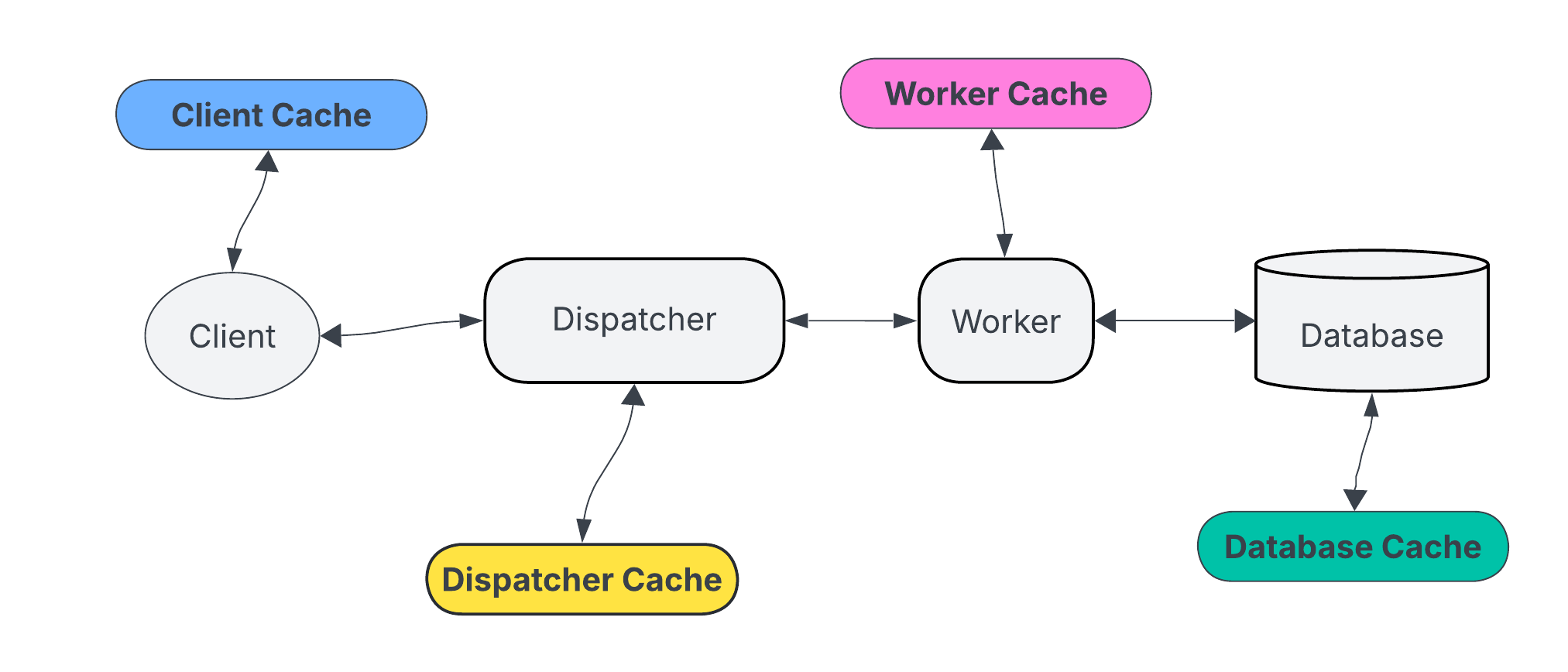

Cache placement in architecture

- Edge caching: content delivery networks serve users from nearby nodes.

- Mid-tier caching: reverse proxies like Varnish or API gateways cache responses.

- Application caching: data or computed results are cached in the service layer.

- Data caching: query results or object serialization cached close to the database.

Common caching strategies

- Cache-aside (lazy loading): the application checks the cache first and loads from the database only if not found, then stores the result in cache.

Cache-aside - Read-through: the cache itself loads data from the source when missing.

Read-through cache - Write-through: writes go through the cache and are immediately persisted to the data store.

Write-through cache - Write-behind: data is written to the cache first and asynchronously persisted later.

Write-behind cache - Refresh-ahead: the cache preloads or refreshes entries before they expire to avoid latency spikes.

Refresh-ahead cache - Write-behind: like write-through, but updates the database asynchronously.

Write-behind cache

Cache invalidation

Invalidation ensures data in the cache stays consistent with the source of truth. It’s one of the hardest parts of caching design.

- Time-based (TTL): entries expire after a fixed period.

- Event-based: updates or deletes trigger cache invalidation.

- Version-based: cache keys include version identifiers that change with updates.

- Manual: explicit cache flush when needed, usually via admin or deployment scripts.

Cache keys and granularity

Cache keys uniquely identify stored data. Design them carefully to avoid collisions or over-caching.

- Use descriptive key patterns like

user:123:profile. - Avoid storing overly large objects — smaller, composable keys improve reusability.

- Namespace keys per environment (e.g.

prod:,staging:).

Eviction policies

- LRU (Least Recently Used): removes the least recently accessed entries.

- LFU (Least Frequently Used): removes items used least often.

- FIFO (First In, First Out): removes oldest entries regardless of access.

- TTL-based: automatically evicts expired entries.

Trade-offs and pitfalls

- Stale data: cache may serve outdated results if invalidation is delayed.

- Cache stampede: many requests recompute the same missing key at once — use locks or request coalescing.

- Memory pressure: unbounded caches can evict hot keys too early or crash under load.

- Cold start: empty caches cause initial latency until they warm up.

Observability and metrics

- Cache hit ratio (hits / total requests)

- Eviction rate and memory usage

- Latency for cache hits vs misses

- Key churn and replication lag (for distributed caches)

Practical guidelines

- Cache only data that is expensive to compute or fetch and changes infrequently.

- Start with simple TTL-based caching before adding complex logic.

- Monitor hit ratios and adjust expiration times based on usage patterns.

- Prefer external caches like Redis for distributed applications.

- Document your caching strategy — keys, TTLs, and invalidation triggers.

Example pattern

// Cache-aside example (simplified)

data = cache.get(key)

if (!data) {

data = db.query(key)

cache.set(key, data, ttl=300)

}

return dataFinal thoughts

Caching is one of the most effective tools to improve performance and scalability in system design, but it introduces complexity around consistency and invalidation. Use it strategically, measure its impact, and treat it as a controlled optimization — not a shortcut for poor design or slow databases.