Availability in System Design — Principles, Patterns, and Practical Guidance

By Oleksandr Andrushchenko, Published on

What availability means, how it's measured, architectural availability patterns, practical trade-offs, and how to validate an availability target.

What is Availability?

Availability is the probability that a system performs its required function at a given point in time. Practically, it answers the question: “Is the service responding correctly when users expect it?”

Availability is often expressed as a percent uptime over a period (e.g., 99.9%). It's related to — but distinct from — durability and correctness.

Simple formula

Availability over an interval = uptime / (uptime + downtime)

// example calculation

uptime = 99.9 // percent

availability = uptime / 100.0 // 0.999 => "three nines"Why availability matters — business & technical impacts

- Revenue & reputation: downtime can directly cost money and user trust.

- Compliance & contracts: SLAs often define penalties for missed availability targets.

- User experience: inconsistent availability degrades engagement and retention.

Measuring availability

- SLA — Promise to customers (e.g., 99.95% uptime).

- SLO — Internal target derived from SLA (e.g., 99.97%).

- SLI — Measured indicator (e.g., successful requests per minute).

- MTTF / MTTR / MTBF: Mean time to failure, mean time to repair, mean time between failures.

Availability = MTBF / (MTBF + MTTR)Failure domains & blast radius

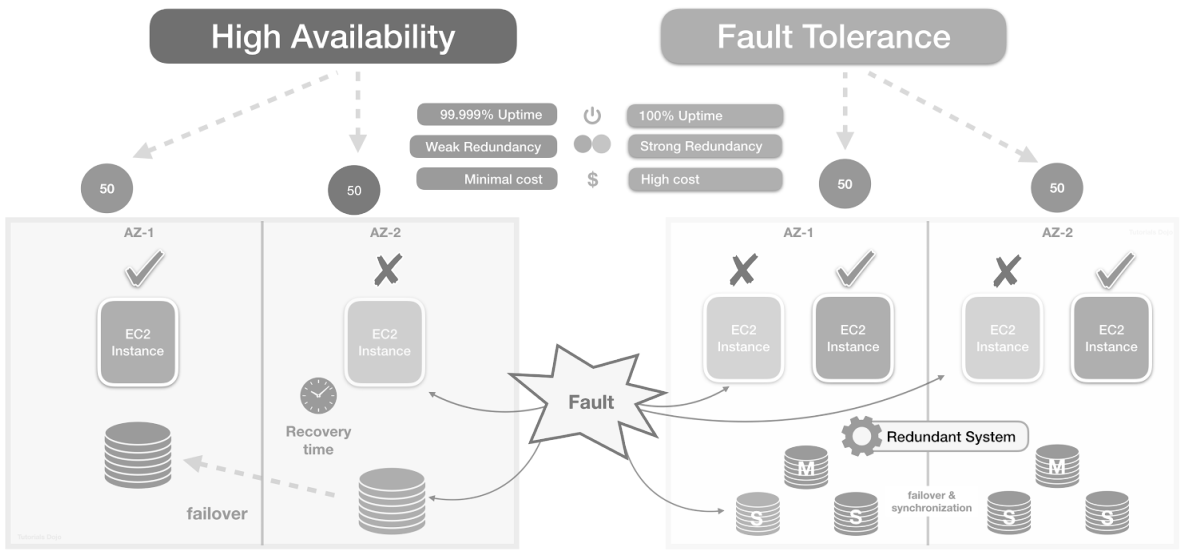

Availability improves by reducing the size of failure domains: server, rack, AZ, region, or cloud provider.

- Minimize single points of failure.

- Use partitioning and isolation to limit blast radius.

Common architectural patterns to increase availability

Replication (leader/follower, multi-master)

Replication increases read availability and can improve write availability depending on mode:

- Leader-follower: simple, good for reads; writes failover requires leader election.

- Multi-master: offers writes in multiple locations but needs conflict resolution and careful anti-entropy.

Active-active vs Active-passive

Active-active: all regions/instances serve traffic; better availability and scaling but more complex (consistency, coordination).

Active-passive: primary serves traffic; standby takes over on failure (simpler but slower failover).

Load balancing & health checks

Use load balancers + health checks to distribute traffic and remove unhealthy nodes automatically. Include layered balancing: local LB (node pool), global LB (region-to-region), and DNS-based failover for disaster recovery.

Graceful degradation & circuit breakers

Prefer returning reduced functionality rather than full failure. Circuit breakers prevent cascading failures by isolating failing subsystems.

Caching & CDN

Caches and CDNs can keep content available during origin outages. Use cache-control and stale-while-revalidate to serve slightly stale content rather than errors.

Queues & asynchronous processing

Buffering requests with durable queues allows handling spikes and partial outages without dropping user work — increases eventual consistency but protects availability.

Geographic redundancy

Serve users from multiple regions for resilience against regional outages—requires replication, DNS failover, or global load balancing.

Database sharding & partitioning

Sharding (horizontal partitioning) splits data across multiple independent database instances to scale writes and limit failure blast radius.

Redundant components

Redundancy means running duplicate components so one can take over when another fails. Design redundancy at multiple layers:

Failover clusters & automated failover

Failover clusters group nodes so that if one node fails, another takes over service duties. Key design points include leader election, state transfer, and split-brain prevention.

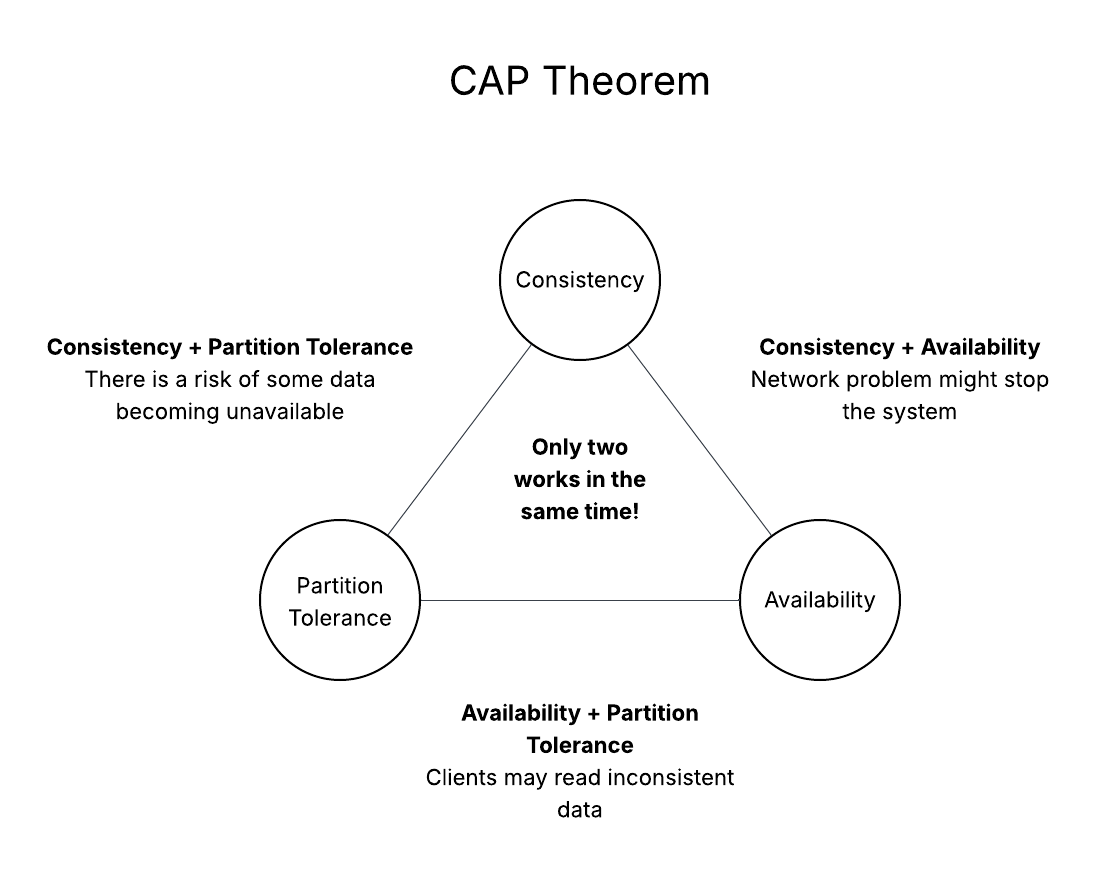

Trade-offs & limitations

Higher availability usually brings higher cost and complexity, and might require relaxing consistency.

| Goal | Typical trade-off |

|---|---|

| Higher availability | More replicas, cross-region traffic, complex failover logic, higher cost |

| Strong consistency | Higher latency or reduced availability during partitions |

| Low latency | Local caches with possible staleness vs global correctness |

Choosing targets: SLA → SLO → design

- Start from the business SLA (what you promise customers?).

- Derive SLOs & SLIs — pick measurable SLIs and an SLO that fulfills SLA with margin for incident windows.

- Design architecture to meet SLOs: replication, sharding, multi-AZ, monitoring, runbooks.

Operational practices to sustain availability

- Observability: SLIs, dashboards, p99/p999 latency, error budgets.

- Runbooks & playbooks: documented, practiced procedures for common failure modes.

- Chaos engineering: proactively test failure scenarios to validate assumptions.

- Automated recovery: health-driven restarts, auto-scaling, infrastructure as code.

- Testing & staging: production-like staging, canary deployments, blue-green or feature flags.

Practical calculations and examples

Combining independent components

Overall availability = product of component availabilities.

A_frontend = 0.9999

A_db = 0.999

A_total = A_frontend * A_db // ~99.89%Redundancy (parallel components)

A_parallel = 1 - (1 - A_single)^NCommon pitfalls

- Ignoring correlated failures.

- Optimizing for average case rather than tail latencies.

- Lack of tested failover procedures.

- Over-engineering availability for low-value services.

Quick architecture checklist

- Define SLA, SLO, SLIs and error budget.

- Identify single points of failure and plan redundancy and sharding.

- Choose appropriate consistency model (CP vs AP tradeoffs).

- Design for failure: health checks, graceful degradation, circuit breakers.

- Automate recovery and practice runbooks.

- Measure tail latency and error rate; allocate error budget for releases.

- Run chaos experiments reflecting realistic correlated failures.